One of the biggest challenges that many photographers face is yielding

sharp photos

when hand-holding a camera. Many end up with blurry images without

understanding the source of the problem, which is usually camera shake.

Unfortunately, camera shake can come from a variety of different sources

– from basic improper hand-holding techniques to mirror and

shutter-induced vibrations that can be truly challenging and sometimes

even impossible to deal with. While I will go over the latter topics in a

separate article, I would like to talk about the most common cause of

camera shake: lower-than-acceptable shutter speed when hand-holding the

camera. I will introduce and explain the reciprocal rule, which can help

in greatly increasing the chances of getting sharp photos when you do

not have a tripod around.

Captured hand-held following reciprocal rule

Sony A7R + FE 35mm f/2.8 ZA @ 35mm, ISO 100, 1/40, f/11

What is Reciprocal Rule?

Due

to the fact that we as humans cannot be completely still, particularly

when hand-holding an object like a camera, the movements caused by our

bodies can cause camera shake and introduce blur to images. The basic

premise of the reciprocal rule is that

the shutter speed of your camera should be at least the reciprocal of the effective focal length of the lens. If you are confused by what this means, don’t worry – it is really easy to understand once you see it in an example.

Say you are shooting with a zoom lens like the

Nikkor 80-400mm f/4.5-5.6G VR (see our

in-depth review) on a full-frame camera like the

Nikon D750 (in-depth review).

All the rule is stating, is that if you are shooting at 80mm, your

shutter speed should be set to at least 1/80th of a second, whereas if

you zoom in to say 400mm, your shutter speed should be at least 1/400th

of a second. Using such fast shutter speeds should prevent blur by

camera shake. Why? Because there is a direct correlation between focal

length and camera shake – the longer the focal length, the more

potential there is for camera shake. If you have a long telephoto zoom

lens like the above-mentioned 80-400mm lens, you have probably already

noticed how much more shaky and jumpy your viewfinder looks when you are

zoomed in to the longest focal length, compared to the shortest one –

that’s because camera movement is magnified at longer focal lengths:

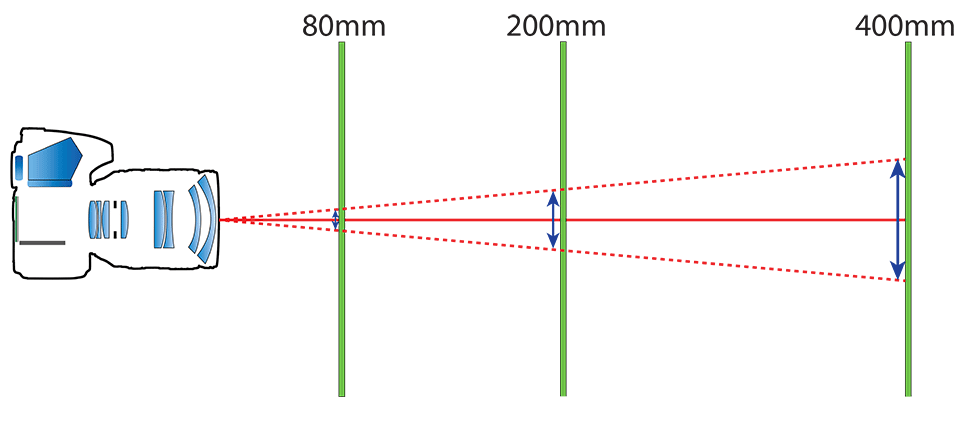

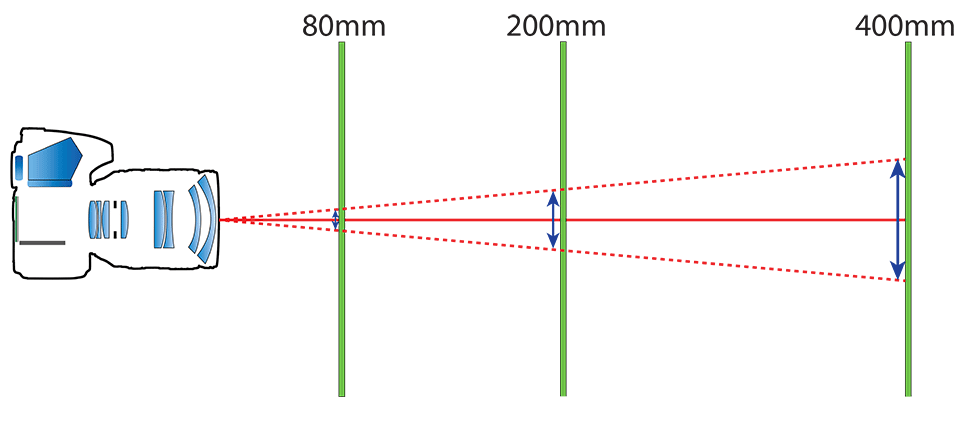

You

can see how the potential for camera shake is increased with the

increase in focal length. The red-dotted lines that represent the

potential limit of how much the camera can shake when hand-held have a

much shorter span at 80mm than at 400mm. That’s because camera shake is

magnified with increase in focal length.

Camera Shake Blur is NOT Motion Blur

It

is important to point out that blur caused by camera shake is very

different than motion blur (where subject is faster than set shutter

speed) – it usually has the whole image blurred, whereas motion blur

might only have the subject, or a portion of the subject appear blurred,

while the rest of the image appears sharp. It is also important to

point out that the reciprocal rule only applies when hand-holding a

camera – mounting your camera on a stable object like a tripod will not

require such fast shutter speeds.

Effective Focal Length

Please

note that I used the word “effective focal length” in the definition

and gave you an example with a full-frame camera. If you have a camera

with a smaller sensor than 35mm / full-fame, (and most entry-level DSLRs

and mirrorless cameras have smaller sensors), you first have to compute

the effective focal length, also known as “equivalent field of view”,

by multiplying the focal length by the

crop factor.

So if you use the same 80-400mm lens on a Nikon DX camera with a 1.5x

crop factor and you are shooting at 400mm, your minimum shutter speed

should be at least 1/600th of a second (400 x 1.5 = 600).

Notes and Exceptions

Although

it is commonly referred to as “reciprocal rule”, it is not a rule per

se – just a guidance for minimum shutter speed to avoid blur caused by

camera shake. In reality, how shutter speed affects camera shake depends

on a number of different variables, including:

- The efficiency of your hand-holding technique:

if you have a poor hand-holding technique, the reciprocal rule might

not work for you and you might need to use faster shutter speeds. Gear

and lenses vary in size, weight and bulk, so you might need to utilize

specialized hand-holding techniques depending on what you are shooting.

For example, check out this great article by Tom Stirr on hand-holding techniques for telephoto lenses.

- Camera resolution:

whether we like it or not, digital cameras are increasing in resolution

and as we have seen in the case of high-resolution cameras like Nikon D810,

having more pixels crammed into the same physical space can have a

drastic effect on how sharp images turn out at 100% zoom. Higher

resolution cameras will show more intolerance to camera shake than their

lower resolution counterparts. So if you are dealing with a high

resolution camera, you might need to increase your shutter speed to a

higher value than what the reciprocal rule suggests.

- Lens quality / sharpness:

you might have a high resolution camera, but if it is not matched by a

high-performing lens with great sharpness, you will not be able to yield

sharp images, no matter how fast your shutter speed is.

- Subject size and distance:

photographing a tiny bird from a long distance and wanting to have

every feather detail preserved usually requires faster shutter speed

than recommended by the reciprocal rule, especially if the subject needs

to be tack sharp at 100% zoom (pixel-level).

- Image stabilization: is a major factor and should be explained separately – see below.

Image Stabilization

Reciprocal

rule falls apart if your lens or your camera come with image

stabilization (also known as “vibration reduction” or “vibration

compensation”), because it effectively reduces camera shake by moving

internal components of a lens or the sensor of the camera. Since the

implementation and the effectiveness of image stabilization depend on a

number of factors including manufacturer technology,

lens vs in-camera image stabilization,

effective use of stabilization technology and other factors, its impact

varies greatly from camera to camera and lens to lens. For example,

Nikon and Canon both use lens stabilization and usually claim between

2-4 times of compensation potential on lenses, whereas Olympus claims up

to 5 times of compensation on its

OM-D E-M1

mirrorless camera with 5-axis in-body image stabilization system.

That’s a pretty big potential for reducing shutter speed to numbers way

below what the reciprocal rule would recommend.

In the above

example with the Nikkor 80-400mm f/4.5-5.6G VR, since the lens comes

with image stabilization and Nikon claims up to 4 stops of compensation,

you could theoretically reduce the recommended shutter speed by

reciprocal rule by up to 16 times! So when shooting at 400mm, if your

hand-holding technique was perfect and you turned image stabilization

on, you could go from 1/400th of a second (reciprocal rule based on a

full-frame camera) to 1/25th of second and still be able to capture a

sharp image of your subject (provided that your subject does not move at

such long shutter speeds and cause motion blur). In such cases,

reciprocal rule simply does not apply…

Applying Reciprocal Rule: Auto ISO

Many

of the modern digital cameras come with a really neat feature called

“Auto ISO”, which allows one to let the camera control

camera ISO

depending on light conditions. Some Auto ISO implementations are rather

simplistic, letting the end-user specify only minimum and maximum ISO

and giving little to no control on minimum shutter speed. Others will

have more advanced Auto ISO features, allowing to specify not only ISO

ceilings, but also what the minimum shutter speed should be before ISO

is changed. Nikon and Canon, for example, have one of the best Auto ISO

capabilities in their modern DSLRs – in addition to the above, minimum

shutter speed can be set to “Auto”, which will automatically set the

shutter speed based on the reciprocal rule:

One

can even customize this behavior further, by decreasing or increasing

the minimum shutter speed relative to the reciprocal rule. For example,

on my Nikon D750 I can set minimum shutter speed to “Auto”, then set the

bar once towards “Faster”, which will double the shutter speed based on

the reciprocal rule. So if I am shooting at say 100mm focal length, the

camera will automatically increase ISO only when my shutter speed drops

below 1/200th of a second. And if I use a stabilized lens and want my

camera to have a longer minimum shutter speed, I can move the same bar

towards “Slower”, reducing the minimum shutter speed guided by the

reciprocal rule.